Humanistic Jewish Role Models

Humanistic Jewish Role Models

The Society for Humanistic Judaism launched the Humanistic Jewish Role Model program in 2005 to create a sense of excitement about outstanding people who demonstrate the organization’s values and philosophy. It provides SHJ affiliates an annual fresh programming opportunity. Additionally, the earlier role models can be used in succeeding years for both adult and children’s programming.

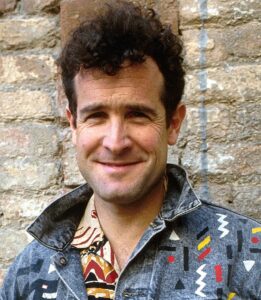

2023-24 Role Model: Johnny Clegg (1953 -2019)

Johnny Clegg was a South African singer-songwriter, anthropologist, and anti-apartheid activist.

He was born in Lancashire, England to an English father of Scottish descent and a mother from Rhodesia whose Jewish parents had immigrated from Lithuania. When he was six months old, his mother moved to Rhodesia. His parents divorced shortly after. When he was six, he and his mother moved to South Africa. Although he knew he was Jewish, he was raised in a secular home and refused a Bar Mitzvah. He even avoided the other Jewish children in the neighborhood.

Jewish parents had immigrated from Lithuania. When he was six months old, his mother moved to Rhodesia. His parents divorced shortly after. When he was six, he and his mother moved to South Africa. Although he knew he was Jewish, he was raised in a secular home and refused a Bar Mitzvah. He even avoided the other Jewish children in the neighborhood.

In his early teens he discovered the music and dance of the Zulu people who were migrant workers in Johannesburg. Clegg mastered the miskandi guitar, isishameni dance and Zulu language. His first collaboration was with a black man named Siphu Mchunu. Associating with other races was against the law, but Johnny was drawn to the music and the people. He was even ticketed for violating these laws.

He attended the University of Witwatersrand and graduated with an Honors BA in Social Anthropology. He pursued an academic career for four years where he lectured and wrote several seminal scholarly papers on Zulu music and dance.

After a time, he and Mchunu went on to form the group Juluka. His singing career was ultimately very successful on a world-wide stage. He went on to perform alone and with another band he formed called Savuka. Although Clegg maintained that his music was not political, it was by its very nature a statement about human rights.

At a concert in 1999, Savuka sang the protest song Asimbonanga that was dedicated to Nelson Mandela. Mandela joined them on stage and danced with the band. You can see that performance at this link.

Johnny Clegg was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015 which ultimately led to his death on 16 July 2019. He died in his Johannesburg home surrounded by loved ones. and was laid to rest the Clegg was survived by his wife, Jenny, and his two sons, Jesse (also a musician) and Jaron.

His autobiography Scatterling of Africa – My Early Years was published posthumously in 2021 by Pan MacMillian in Johannesburg.

2022-23 Role Model: Harvey Milk (1930-1978)

This year’s Role Model is Harvey Bernard Milk, an American politician and the first openly gay elected official in the history of California, where he was elected to the San Francisco Board of  Supervisors.

Supervisors.

Milk was born on May 22, 1930 in the New York City suburb of Woodmere, to William Milk and Minerva Karns. He was the younger son of Lithuanian Jewish parents and the grandson of Morris Milk, a department store owner, who helped to organize the first synagogue in the area.

During the peak of his political career, Harvey Milk supported anti-discrimination bills, free public transportation, and the development of a board of civilians to oversee the police. He supported the establishment of day care centers for working mothers, the conversion of military facilities into low-cost housing, and spoke out on state and national issues for LGBT peoples, women, racial and ethnic minorities and other marginalized communities.

Tragically, Milk was assassinated, along with mayor of San Francisco, George Moscone, on November 27, 1978 by a former member of the Board of Supervisors.

Sharyn Saslafsky, who met Milk through politics and then became a close friend, remembers sitting with him on an old maroon sofa in Castro Camera having conversations peppered with Yiddish while opera blared in the background. Like others, she recalls him as “very much a cultural Jew.” “I think Harvey was very proud of being both Jewish and gay. He loved what Judaism and tikkun olam was about,” Saslafsky said. “I think the basis of who Harvey was personally and politically was really very Jewish in the sense of being active and making a difference, taking responsibility, empowering people. I look at that as very Jewish-like.”

Milk was very critical of organized religion and did not attend religious services. Randy Shilts wrote in The Mayor of Castro Street (2008) that “Harvey never had any use for organized religion.” In one of his recorded wills, Milk said of his funeral: “I hope there are no religious services. I would hope that there are no services of any kind, but I know some people are into that and you can’t prevent it from happening, but my god, nothing religious . . . I would turn over in my grave.” Harvey was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his iconic, influential and albeit short career. That same year Harvey was inducted in the California Hall of Fame, with May 22 designated as “Harvey Milk Day.”

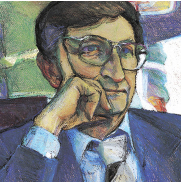

2021–22 Role Model: Yaakov Malkin (1926–2019)

We are pleased to name Yaakov Malkin as the 2021-22 Humanistic Jewish Role Model of the Year. Malkin was the provost of the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism (IISHJ) since the death of Sherwin Wine and of Tmura, the IISHJ based in Jerusalem since its inception. Malkin’s support of the movement was exceptional and our gratitude is great. We are privileged to honor him and his legacy.

We are pleased to name Yaakov Malkin as the 2021-22 Humanistic Jewish Role Model of the Year. Malkin was the provost of the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism (IISHJ) since the death of Sherwin Wine and of Tmura, the IISHJ based in Jerusalem since its inception. Malkin’s support of the movement was exceptional and our gratitude is great. We are privileged to honor him and his legacy.

Yaakov Malkin was an educator, writer, literary critic, and professor emeritus in the Faculty of Arts at Tel Aviv University. Professor Malkin taught comparative literature, aesthetics, theater, and film criticism, and co-founded the Department for Cinema and Television at Tel Aviv University. He was a founder of the Jewish Center movement in Israel. He also founded and directed two Jewish-Arab community centers in Haifa, the first of their kind, and published several texts on community, education, and public speaking. Among his many books are Judaism Without God and Epicurus and Apikorsim available through the SHJ here and Secular Jewish Culture on Amazon here.

Malkin was an original and powerful spokesperson for the Secular Humanistic Jewish movement. Malkin dedicated his writings to the humanistic beliefs shared by the non-religious community in the West generally, and among the Jewish people in particular. Malkin claimed that there are no nonbelievers, but rather people who express a variety of beliefs in their day-to-day lives. These can include religious beliefs, characterized by a commitment to follow religious leaders who claim to speak in the name of a god, or nonreligious beliefs, which include the belief in humans as creators of their own paths and behaviors, whether as individuals or in society, with the goal of attaining the purpose of human life: happiness.

In a description of the differences between religious and secular beliefs and approach, rarely made so clearly, Malkin maintained that a distinction must be made between two types of faith in reality. Rational faith (belief) in reality is the name for attributing truthfulness to a description or process that has been proven scientifically through experiments and research. Religious faith in reality is the name for attributing truthfulness to a description or process because it is written in a holy book of a certain religion.

Furthermore, he upheld that a distinction must be made between two types of faith in ideal. Rational faith (belief) in an ideal is the name for attributing a person’s commitment to act according to universal rules of justice. Rules of justice, which fulfill human rights, in order to improve the life of the individual and the community, to lessen suffering and increase pleasure in life. Religious faith (belief) in an ideal is the name commitment to behavior dictated by the commandments of certain religious leaders who aspire to speak in the name of the god of that religion.

Malkin was a prolific writer, playwright, sought after speaker, and a mensch.

2020–21 Role Model: Helen Suzman (1917–2009)

It seems especially fitting that in this year of seeking racial justice that our Humanistic Jewish Role Model for 2020-21 is longtime anti-apartheid activist South African MP Helen Suzman. Born Helen Gavronsky, the daughter of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants, she ultimately became a professor of economic history.

Helen’s nephew. Paul Suzman shares his memories of his aunt in conversation with Dr. Richard Logan at this link.

Suzman was elected to parliament in 1953, several years after apartheid was declared. A few years later, she and eleven other deputies formed the activist Progressive Party in 1959. The Progressives called for the gradual enfranchisement of blacks, for abolition of internal passports and the legalization of black trade unions. But, being too liberal for most of white South Africa, all eleven Progressive deputies except Suzman lost their seats in the next election. She thus became the lone parliamentary voice against apartheid from 1961 to 1974. It was during these years that Suzman made her international reputation as a champion of human rights. In 1961, she protested the Sharpeville massacre of sixty-nine blacks for demonstrating against the internal passport system, and against draconian measures in its aftermath. In 1963, the South African government arrested Nelson Mandela, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), along with nine of his white supporters, primarily Jews. Suzman visited Nelson Mandela frequently serving a life sentence on Robben Island. Thanks to her persistence, Mandela received more humane treatment.

Watch a presentation about Helen Suzman’s amazing life by Rabbi Adam Chalom, Dean, North America of the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism.

Suzman exemplified and championed the human rights and social justice that we as humanists value and support, but she also brought to bear Jewish values and the Jewish historical experience; viz, “…. [M]y knowledge of the Jewish experience of persecution heightened my awareness of the evils of discrimination.” And, “…. [S]upporting race discrimination was the ultimate treachery of [Jewish] values ….”. Her life also clearly exemplified tikkun olam. A secular Jew, Helen Suzman was known to say that her primary identity was as a secular humanist. She also embraced reason and evidence-based thinking, as witness her eloquent addresses to the South African parliament on the conditions of black South Africans under apartheid.

While Suzman’s primary focus was the struggle against apartheid, she also worked for women’s rights by supporting legislation to guarantee equality in marriage and divorce, reproductive rights, and protection from rape. Throughout her career, Suzman was frequently subjected to abuse from National Party deputies, who used anti-Semitic slurs and attacked her as a communist, and a “sickly humanist.” Her phones were tapped and she was the target of numerous death threats. But she stood her ground. For example, when Afrikaner Prime Minister Vorster chastised her for spending so much time in Soweto, the most populous black township, she answered, “You might try going to Soweto yourself one day. But go disguised as a human being.”

Suzman visited Israel a few times, and in 1988 she demonstrated against attempts to narrow the Law of Return to conform to the Orthodox definition of who is a Jew. In 1993, she received the Nahum Goldman Award from the World Jewish Congress. She also received twenty-seven honorary doctorates from universities around the world, including Harvard, Yale, Oxford and Cambridge. She was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and received numerous other awards from international bodies.

Nelson Mandela, who had become South Africa’s first black South African president in 1994, wrote this message to Helen Suzman on her 85th Birthday: “Your courage, integrity and principled commitment to justice have marked you as one of the outstanding figures in the history of public life in South Africa”. We would amend this to read“ …. the outstanding Jewish and humanist figure in the history of public life in South Africa….”.

2019–20 Role Model: Amos Oz (1939–2018)

Amos Oz was born Amos Klausner May 4, 1939 in Jerusalem. Oz was a novelist, short-story writer and essayist, as well as a professor and a prominent peace advocate.

He was the only child of Fania (Mussman) and Yehuda Arieh Klausner, immigrants to Mandatory Palestine who had met while studying at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. When he was 12, his mother committed suicide. At age 14, he became a Labor Zionist, left home and joined Kibbutz Hulda. He studied at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, earning a degree in Hebrew Literature. After completing his mandatory three year service In the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), he continued as an army reservist in a tank unit which fought in the Sinai Peninsula during the Six-Day War, and in the Golan Heights during the Yom Kippur War. In 1960, he married Nily Zuckerman. They had three children together and continued to live on the Kibbutz until in 1966, the family moved to the Negev for his son’s health.

Amos Oz was best known as a writer. In addition, he taught Hebrew Literature at Ben Gurion University for more than a decade. Oz published 40 books, among them 14 novels, five collections of stories and novellas, two children’s books, and twelve books of articles and essays (as well as eight selections of essays that appeared in various languages), and about 450 articles and essays. His works have been translated into some 45 languages, more than any other Israeli writer. Oz is the recipient of a number of awards and prizes, including the 1986 Bialik Prize and the 1998 Israel Prize for Literature.

Brittanica.com articulated his great gift, “Oz’s symbolic, poetic novels reflect the splits and strains in Israeli culture. Locked in conflict are the traditions of intellect and the demands of the flesh, reality and fantasy, rural Zionism and the longing for European urbanity, and the values of the founding settlers and the perceptions of their skeptical offspring. Oz felt himself unable to share the optimistic outlook and ideological certainties of Israel’s founding generation, and his writings present an ironic view of life in Israel.”

Following the Six Day War, Oz joined the Israeli peace movement and was one of the first to advocate for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He was outspoken against Israeli settlements on the west bank and supported the Oslo accords and direct talks with the PLO. He became well known for his political activism.

Amos Oz was not religious and considered himself a secular Jew. He did not attend synagogue nor did he have any use for worship. However, he understood Judaism profoundly. In describing Judaism Oz once said, “Judaism is not a package deal. It is a heritage. And a heritage is something that you can play with. You can decide which part of the heritage you allocate to your living room, and which part goes to the attic or the basement. This is the legitimate right of every heir.”

Oz is an ideal choice to be the Humanistic Jewish Role Model for 2019-2020. His deep connection to Judaism, albeit a secular one, his commitment to living his humanistic values, and his connection to the Secular Humanistic Jewish movement in Israel make him easily worthy of this honor.

2018–19 Role Model: Grace Paley (1922–2007)

Grace Paley, born in 1922, was an American short story writer, poet, teacher, and political activist. Born in the Bronx, New York, Paley was the youngest child of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. She grew up in a socialist, intellectual family that spoke three languages — Yiddish, Russian, and English. Typical of such families, Jewish identity was grounded in family and community relationships and socialist politics, rather than in synagogue life.

Paley taught creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College and City College of The City University of New York, and was also the first official New York State Author. For her Collected Stories, Paley was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction; she was also a recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship for Fiction and the Rea Award for the Short Story.

Paley was known for pacifism and for political activism. She classified herself as a “somewhat combative pacifist and cooperative anarchist,” a label that stuck. Her pacifism led her to help found the Greenwich Village Peace Center in 1961. With the escalation of the Vietnam War, Paley joined the War Resisters League. In 1968, she signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War, and in 1969 she came to national prominence as an activist when she accompanied a peace mission to Hanoi to negotiate the release of prisoners of war. Paley spent time in jail for her anti-war activities.

Her fictional characters were rooted in modern Jewish life. They were not religious, but they were Jewish, struggling with the issues of the day. When she lived in New York, her life-style and her Jewish identity were one and the same. But, later in life, after moving to Vermont, she became more connected to religious Judaism. “‘I often go [to services] on the High Holy Days,” Paley said. “In New York, I didn’t, but here the towns are very church-centered — the church is like the community center, and I’m not in it. If I didn’t have the Jewish community, I’d be lonesome.”

Paley was chosen as the SHJ 2018–19 Humanistic Jewish Role Model because her values were expressed in action. She did not look to a higher power to solve the issues and problems of the day. Her behavior reflected her secular belief system. She was Jewish through and through and when she moved to Vermont, away from New York City where you could express your connection to being Jewish in the streets, she sought out Jewish community where she could find it, rather than abandoning her identity.

2017–18 Role Model: Gene Wilder (1933–2016)

Gene Wilder was born Jerome Silberman on June 11, 1933 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to a Jewish Immigrant father and a mother born in Chicago. His mother died when he was 14 and he had one sister. He graduated from Washington High School in Milwaukee and studied Communication and Theatre Arts in college, graduating from the University of Iowa. Married four times, famously to Gilda Radner for five years before she died of cancer, and finally to Karen Boyer from 1991 to his death in August 2016, due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease. He was best known for his roles in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, Blazing Saddles, Frisco Kid, The Producers and Young Frankenstein.

Wilder was raised Jewish. In Stars of David, a book published in 2005 and written by Abigail Pogrebin he stated, “I have no other religion. I feel very Jewish and I feel very grateful to be Jewish. But I don’t believe in God or anything to do with the Jewish religion.” He often described himself as a “Jewish-Buddhist-Atheist.” His lack of religious beliefs aside, he was unapologetically proud and grateful about being Jewish and said he carried his Jewish identity with pride.

2016–17 Role Model: Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958)

Rosalind Franklin was a British chemist renown for her work in the use of X-ray diffraction and the significant role one of her photographs played in the discovery of the structure of DNA. She also invented carbon fiber technology. Franklin was born in 1920, the second of five children, in London England, to a well to do Jewish family. Her family took in and saved two Jewish children during World War II. Her exceptional intelligence was noted early in her life. She ultimately achieved a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Cambridge. Franklin felt the full force of both anti-Semitism and sexism when she worked at King’s College. She learned that she was to serve as the research assistant to a male colleague, when, in fact, the research was a result of her own genius and hard work. The major controversy in her professional life occurred when her colleague at King’s College shared her research, without her knowledge with scientists Watson and Crick at Cambridge University who went on to earn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of DNA’s double helix. Playright Anna Ziegler, in her play about Franklin called “Photograph 51” characterized her as staunchly secular, with a strong sense of wonder. Tragically, she died at the age of 38 of ovarian cancer.

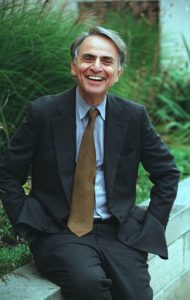

2015–16 Role Model: Carl Sagan (1934–1996)

2015–16 Role Model: Carl Sagan (1934–1996)

Carl Sagan was a brilliant, award-winning scientist whose unique place in history was as a translator of hard science to the language of the heart. In books, innumerable articles, television and film, his work inspired wonder, and the possibility that we could know our immense, mysterious and ever-expanding universe through reason and science. In his groundbreaking Cosmos series on television during the 80’s and subsequent book and film Contact, Sagan spread a humanistic worldview to ordinary people all over the world—a view where neither religion nor nationality could separate people from nature, one another, or the universe at large. Sagan, a cultural Jew at home, was in his public life a proud and eloquent citizen of Planet Earth.

2014–15 Role Model: Nora Ephron (1941–2012)

2014–15 Role Model: Nora Ephron (1941–2012)

Nora Ephron was known for her caustic wit, biting sarcasm, brutal honesty, and her innovative sense of humor as a reporter, essayist, playwright, and screenwriter. Her credits include countless essays, plays, the iconic films When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and You’ve Got Mail, and her autobiographical book, Heartburn, which was turned into a movie. Her family were secularists and incidental Jews. She bristled at being pegged a “Jewish director,” just as she cringed at being described as a “woman director”: “It seems like a narrow way of looking at what I do.” She was neither an observant or strongly self-identified Jew. “You can never have too much butter—that is my belief. If I have a religion, that’s it,” she quipped in an NPR interview about her 2009 movie Julie & Julia. In 1994, she received the Women in Film Crystal Award. After her death from leukemia in 2012, the Tribeca Film Festival established the Nora Ephron Prize, which awards $25,000 to a female writer or director “with a distinctive voice who embodies [her] spirit and vision.”

2013–14 Role Model: Maurice Sendak (1928–2012)

2013–14 Role Model: Maurice Sendak (1928–2012)

Maurice Sendak, a well-known writer and illustrator of children’s books, is an attractive multi-generational choice for a role model. Sendak’s work is ostensibly for children, but it also touches on issues and feelings faced by adults. His Jewish identity forms the context of his story telling. Sendak’s most well-known children’s book is Where the Wild Things Are, for which he received the Caldicott Medal. He preserved the memory of his deceased relatives, using their pictures as the basis of his illustrations for Isaac Bashevis Singer’s book, Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories. He also collaborated with playwright, Tony Kushner, illustrating Hans Krasa’s Brundibar, a children’s opera about a brother and sister who fight a bully named Brundibar. Sendak was an atheist and stated in a September 2011 interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio’s Fresh Air that he didn’t believe in God.

2012–13 Role Model: Richard Feynman (1918–1988)

Feynman (pronounced “Fineman”) was an American physicist known for his theoretical work in quantum mechanics, quantum electrodynamics, and particle physics. A professor at the California Institute of Technology, he pioneered in the field of quantum computing and introduced the concept of nanotechnology. A 1965 Nobel Prize winner in Physics for work on quantum electrodynamics, he has been called one of the ten greatest physicists of all time. He authored several popular books, including Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! and What Do You Care What Other People Think? Born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents, Feynman was a self-proclaimed atheist with an irreverent sense of humor. He wrote that at age 13 he “stopped believing that the Jewish people are in any way ‘the chosen people.’”

Feynman (pronounced “Fineman”) was an American physicist known for his theoretical work in quantum mechanics, quantum electrodynamics, and particle physics. A professor at the California Institute of Technology, he pioneered in the field of quantum computing and introduced the concept of nanotechnology. A 1965 Nobel Prize winner in Physics for work on quantum electrodynamics, he has been called one of the ten greatest physicists of all time. He authored several popular books, including Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! and What Do You Care What Other People Think? Born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents, Feynman was a self-proclaimed atheist with an irreverent sense of humor. He wrote that at age 13 he “stopped believing that the Jewish people are in any way ‘the chosen people.’”

2011–12 Role Model: Ernestine Rose (1810–1892)

The nineteenth-century activist Ernestine Rose was an ardent abolitionist, a spokesperson for women’s rights long before Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton appeared on the scene, a socialist in a capitalist country, and an atheist at a time when many Americans turned to their Bibles for guidance. Ernestine Rose was one of our more intriguing Humanistic Jewish Role Models. Many of our members learned of her for the first time through this project, and they felt the excitement of discovering a Jewish woman who demonstrated the philosophy and values of Humanistic Judaism long before Humanistic Judaism existed.

2010–11 Role Model: Jonas Salk (1914–1995)

Jonas Salk, a medical researcher and virologist, developed the first safe and effective polio vaccine. Born to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, Salk was a cultural Jew whose Jewishness was a deeply important aspect of his life. He wrote: “Curiosity was very much a part of my early life: asking questions about unreasonableness. I tended to observe, and reflect and wonder. That sense of wonder, I think, is built into us.”

2009–10 Role Model: Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677)

Baruch Spinoza, the seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher, laid the ground-work for the Enlightenment and for modern biblical criticism. Spinoza identified God with the totality of the universe and maintained that the Bible was not a revealed document but was written by human authors. He was excommunicated by Amsterdam Jewish authorities for his unorthodox beliefs.

2007–08 Role Model: Sherwin Wine (1928–2007)

Rabbi Sherwin T. Wine was the founder of Humanistic Judaism and a chief architect of the international movement known as Secular Humanistic Judaism. Wine combined the philosophy of Humanism, an attachment to Jewish culture, and congregational life to create a new, modern approach to Jewish identity. Welcoming and inclusive, Rabbi Wine championed the rights of all individuals to marry the person they loved regardless of their gender or their religious or cultural background. Wine officiated and co-officiated at weddings for couples from different religious backgrounds, invited non-Jewish individuals to become full members of his congregation and the Humanistic Jewish movement, and encouraged self-definition as the measure of membership in the Jewish people.

2006–07 Role Model: Betty Friedan (1921–2006)

Betty Friedan was the author of The Feminine Mystique (1963), which sparked the feminist revolution. Friedan was the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), which she founded. Earlier in life, she was active in Jewish circles; she attributed her “passion against injustice” to her “feelings of the injustice of antisemitism.”

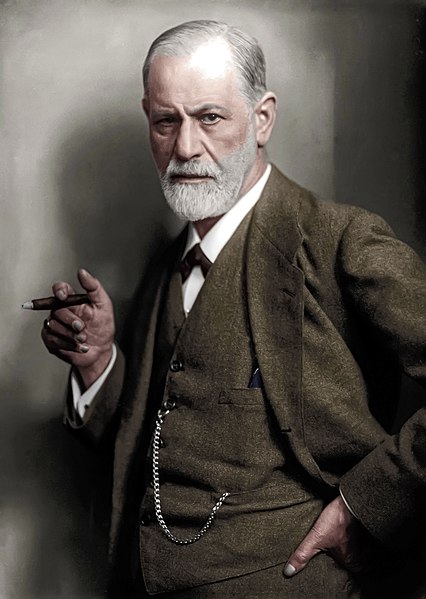

2005–06 Role Model: Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

Sigmund Freud is known as the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud rejected religion as an illusion but embraced Jewish peoplehood. Although Freud’s theories are controversial today, his formidable achievements in medicine and psychology and his wide-ranging impact on contemporary understandings of human nature are undeniable.

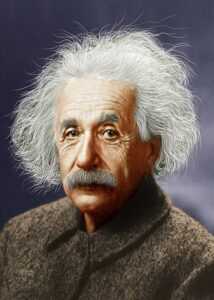

2004–05 Role Model: Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

Albert Einstein is often called the father of nuclear physics. Einstein believed that human power and responsibility are the foundations of morality, reality is limited to the natural universe, and supernatural intervention plays no part in its events. While rejecting a personal God, he was proud of his Jewish heritage, especially “the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, an almost fanatical love of justice, and the desire for personal independence.”