This article was published in the Winter 2022 Issue of Humanistic Judaism Magazine. It was written by Paul Golin, Executive Director of the Society for Humanistic Judaism.

Pluralism can be defined as the respectful inclusion of multiple groups holding differing or even competing worldviews and ideals. Seems like a no-brainer of a positive value. Isn’t inclusion always preferable to exclusion?

Pluralism can be defined as the respectful inclusion of multiple groups holding differing or even competing worldviews and ideals. Seems like a no-brainer of a positive value. Isn’t inclusion always preferable to exclusion?

One challenge is in implementation. The wider the spectrum of worldviews, the more difficult it is for all involved to feel genuinely included. And Jewish identity is a pretty wide spectrum. Another challenge is whether all groups merit inclusion. At some point there must be parameters of who’s in and who’s out, unless the focus is all of humanity.

There are a number of notable attempts at pluralism in the North American Jewish community. Arguably the most important is the local Jewish federation system, which serves as a fundraising umbrella supporting Jewish non-profits regardless of denomination, ranging from Orthodox day schools to Humanistic Judaism congregations—a number of which have received federation grants. Likewise, Jewish Community Centers (JCCs) see their work as cultural, non-denominational, and open to all.

Less common are Jewish organizations where pluralism is the central goal. Limmud hosts Jewish learning conferences where participants of any background or belief are not only invited to attend, but also invited to present on their differing Jewish perspectives. Civil dialogue about potentially divisive issues is celebrated. Several leaders in our movement have presented at Limmud gatherings. One of my sessions at Boston Limmud was titled, “There Is No God and I’m Still Jewish.” It was a fun, friendly, well-attended conversation despite the (hopefully) provocative title.

A Seat at the Table

Coalitions can also create pluralistic spaces. Not long ago, the Society for Humanistic Judaism became a member of the Jewish Social Justice Roundtable, which brings together organizations committed to progressive causes. The Roundtable includes the organizing bodies of Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist, and Renewal Judaism, as well as at least one Modern Orthodox social justice group and many unaligned Jewish organizations focused on issues such as women’s equality, LGBTQ inclusion, and climate change.

While Humanistic Jews may have been marginalized from the organized Jewish community in the past, I am happy to report that I’ve never been made to feel a lesser member of the Jewish Social Justice Roundtable. There is a growing awareness of just how many Jews (and Americans in general) are secular in outlook, and that being secular doesn’t mean a person has given up their Jewish identity. Humanistic Judaism can speak to the wider Jewish community on behalf of many such folks’ interests and concerns.

By being in a working relationship with peers on the Roundtable, I’m forced to grapple with their beliefs and motivations, including their religious convictions. We find common ground and see the humanity in one another, even when holding strongly divergent worldviews. Granted, we are coming together around social and political causes on which we’ve found consensus, and all the people involved are kind and empathetic, so it’s not like I’m walking through the lion’s den of pluralistic challenges! Still, after each meeting, I come away energized by the potential of Jewish pluralistic cooperation. I feel it’s some of the most important work I do.

I’d also like to believe the Jewish Social Justice Roundtable’s spectrum of pluralism has been stretched by our presence, and the work of some of their member organizations has been made more inclusive of secular and Humanistic Jews. For example, I’ve asked for changes to commonly used language in joint sign-on statements: instead of “because we were all created in God’s image,” I’ve suggested, “because Jewish tradition teaches that we were all created in God’s image.” I understand the political advantage in bringing our religious heritage to the fight for equality, but the former phrase is supernatural speculation presented as truth and I can’t sign it. The revised version is historical fact that all Jews can agree upon.

Likewise, I’ve asked for the seemingly pluralistic phrase “as people of faith” be broadened to include a secular outlook, “as people of faith and conscience.” Language matters, perhaps more to Humanistic Jews than anyone. It feels validating when our partners are willing to tweak language to include us. And they’ve expressed nothing but appreciation for the correctives, as they want to be more inclusive.

A Part of Pluralism, but Not Pluralistic

Our movement is an essential piece of a pluralistic Jewish tapestry. That said, it is important to acknowledge that Humanistic Judaism itself is decidedly not pluralistic. And we shouldn’t try to be! We’re not for everyone, and that’s okay. We are a denomination founded by, for, and about atheist/agnostic/ignostic/science-based/freethinker/skeptic/secular/“spiritual not religious”/and/or Humanistic Jews—plus our loved ones. We don’t turn people away, we welcome all, but if nobody in a household identifies as one or more of these labels, their Jewish socio- intellectual needs are likely better served elsewhere in the community.

Even for those who do identify with one or more of the above labels, if they still seek theistic prayer or want to use the traditional liturgy for whatever reason (and there are plenty of valid reasons), again, they are likely better served elsewhere—and in fact can get that prayer service pretty much everywhere else in the Jewish community. Secular Humanistic Judaism is the only space providing Jewish holiday celebrations and lifecycle events for folks who don’t want to hear any God language and only want to “say what we believe and believe what we say.”

Are accommodations made at times for unique circumstances? Of course. But the expectation should be that Humanistic Jewish communities provide Humanistic Judaism to primarily Humanistic Jewish households. I wouldn’t walk back into the Conservative synagogue of my youth and demand that they now accommodate my theology by using a Humanistic Sh’ma. They’re not pluralistic in that way, and neither are we. And that’s all good! Together, the various denominations and expressions of Jewish life can serve the full plurality of Jewish households.

Serving the full plurality of Jewish households, though, means including Humanistic Jews in wider pluralistic settings. If our local JCC or federation is hosting a community-wide Hanukkah party, could we ask that a Humanistic menorah-lighting blessing be read alongside the traditional theistic version? Probably not, if we’re walking in off the street for the first time. But what if we are already deeply involved in their work, or if we have overlapping lay leadership? That makes it much more likely.

While not pluralistic as a movement, we can still convene pluralistic events and programs ourselves—as all Jews can, since we are all part of the whole—and in fact SHJ operates a pluralistic Jewish social justice initiative, Jews for a Secular Democracy (JFASD). The goal of the Jews for a Secular Democracy initiative is to bring multi denominational Jewish perspectives to the defense of American church-state separation. For example, JFASD can advocate for reproductive justice through both the Jewish religious tradition on abortion (which has never seen life beginning at conception) and secular Jewish perspectives (which may call for medical knowledge and individual and societal health as the only relevant factors, not religious interpretation). By serving as convener of this pluralistic initiative, we guarantee our own inclusion as Humanistic Jews. And we demystify Humanistic Judaism for our participants and partners from other expressions of Judaism, who learn that we are all in common cause, even if we take different avenues to the same conclusions.

Hosting Pluralism Requires Compromise

Since working at SHJ, I’ve come to recognize how much healthier it is for my own psyche to be advocating full-throated for my kind of Judaism, rather than remaining neutral or having to present all approaches as equally valid.

Prior to 2016, I spent sixteen years in various roles at a pluralistic organization called Big Tent Judaism/Jewish Outreach Institute. The mission was to work across denominational and institutional lines to help the whole Jewish community become more inclusive, particularly toward intercultural and interfaith households.

Intermarriage is of course one of the most divisive issues in the Jewish community. While I’m proud of Big Tent Judaism’s accomplishments as a small organization stewarding the positive shift that did occur among North American Jewry on the issue, there were many instances when I held my tongue and even felt marginalized in the service of pluralism.

For example, at times I found myself defending against claims that intermarriage is “the single greatest threat to the Jewish people.” I was supposed to understand such hyperbole as nothing but a theoretical construct, yet as an intermarried Jew myself, how could I not take it personally? It often seemed like I was the only intermarried person in the room—which was quite possible, considering one study we did showed that while half of all married Jews in America are intermarried, only 10% of married Jewish communal professionals are intermarried.

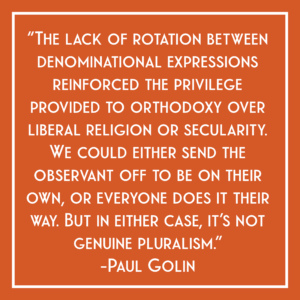

When hosting pluralistic conferences and events, we came to recognize a phenomenon jokingly referred to as the Frummest Common Denominator (“frum” is an expression for ultra-Orthodoxy). If we were serving food, it had to be the highest level of kosher, with the most traditional version of prayer before and after meals and Orthodox Shabbat rules followed. On the one hand, it made sense that the less strict had the flexibility to accommodate the most observant: because I could eat both kosher and non-kosher food, no problem eating kosher. On the other hand, the lack of rotation between denominational expressions reinforced the privilege provided to orthodoxy over liberal religion or secularity. We could either send the observant off to be on their own, or everyone does it their way. But in either case, it’s not genuine pluralism.

As intermarried, secular Jews are so regularly marginalized or disengaged from organized Jewish life, I often felt like an envoy from an alien planet when consulting with synagogues, JCCs, and federations. To their credit, most Jewish communal professionals wanted to identify and address the many barriers to participation they were either purposely or inadvertently maintaining. Several institutions, particularly Conservative synagogues, felt their hands were tied by their understanding of Jewish law (halacha). Over time it grew increasingly more difficult for me to respect what I came to see as hypocrisy, considering how many other Jewish laws or traditions they reworked, all for the better (women rabbis; officiating at gay weddings; accepting patrilineal descent in Reform and Reconstructionism, etc.).

As intermarried, secular Jews are so regularly marginalized or disengaged from organized Jewish life, I often felt like an envoy from an alien planet when consulting with synagogues, JCCs, and federations. To their credit, most Jewish communal professionals wanted to identify and address the many barriers to participation they were either purposely or inadvertently maintaining. Several institutions, particularly Conservative synagogues, felt their hands were tied by their understanding of Jewish law (halacha). Over time it grew increasingly more difficult for me to respect what I came to see as hypocrisy, considering how many other Jewish laws or traditions they reworked, all for the better (women rabbis; officiating at gay weddings; accepting patrilineal descent in Reform and Reconstructionism, etc.).

Gradually and over many years, I was able to find my voice, and it was more radical than most of the organized Jewish community’s. When I started working on interfaith marriage, my goal was to demonstrate that intermarried households could look and behave just like in-married (two Jewish spouses) households, if only they were able to engage fully in Jewish communal life. My conclusion morphed to recognize that, no, intermarriage is changing Judaism. It is making multiculturalism a higher value than ethnocentricity, and universalism a higher value than Jewish supremacy. And that’s something to celebrate not just accept. There is really only one spunky little denomination that currently accommodates such viewpoints, and I’m lucky enough to currently work for it!

We Shouldn’t Compromise Integrity

If the above is the good and the bad, here’s the ugly side of Jewish pluralism: Jews may ultimately be on too wide a spectrum to collaborate pluralistically without some of us greatly compromising our morals. And this cuts both ways. One of the Jewish organizations most celebrated for “pluralistic” learning and dialogue has a president who has said atheist Jews are beyond the pale of the community.

Our movement has long known what it is like to be marginalized out of supposedly pluralistic settings that only runs from ultra-Orthodoxy to Reconstructionism, stopping where theistic prayer ends. Frankly, I find it sickening that some might exclude atheist/agnostic Jews (22% of American Jewry) but still keep within their pluralistic tent sects of ultra-Orthodoxy (~7%) that insist their Jewish heritage requires a grown man to put his mouth to the wound of an infant’s circumcision (metzitzah b’peh), cruelly swing a live rooster over their heads before slaughtering it as a stand-in for their sins (kapparot), withhold secular education from their children, and relegate women to such a status as to not even publish photos of female world leaders in their newspapers.

This isn’t a difference of opinion, it’s a clash of worldviews. It is a battle over a future informed by the scientific method or ancient superstitions. Klal Yisrael, the unity of all Jews, is less important to me than universal human dignity. At some point it is okay to say that no, we are not “all one” Jewish people. Maybe acknowledging there are different Jewish peoples (plural) is a healthier way to move forward.

Because ultimately, humanistic values really are different than Jewish religious values. While that difference is most clear between us and Haredi Jews, at times I can’t help but worry that liberal Jewish denominations provide cover for the worst aspects of religious Judaism by insisting on speaking in the same terminology, and not recognizing that so many of their recent changes are due to their own humanistic values allowing them to amend past religious approaches.

I will continue sharing humanism as a philosophy in the hopes that liberal religious Jews will recognize it in themselves. But there’s little point in being critical of their religious rationale, despite my concerns, when we are in common cause for the same (humanistic) outcomes: equality for all people, human rights, environmental protection, fighting anti-Semitism, and so much more.

As alluring the pull of being a hardcore secularist sometimes is, there’s just not enough of us (yet) to repair the world on our own. We must be in coalition with liberal religion. And therefore yes, Jewish pluralism is an essential goal. But whatever the reasons are for coming together pluralistically, it must be informed by some shared common values. Just as tolerant societies can paradoxically ban the intolerant, effective Jewish pluralism is usually on a narrower spectrum than “all the Jews.”

Leave a Reply