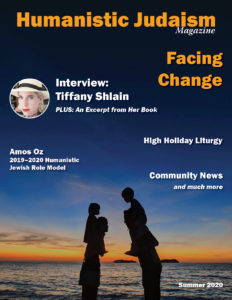

Tiffany Shlain is an Emmy-nominated filmmaker, founder of the Webby Awards, and author of the best-selling book about her family’s decade long practice of turning off screens one day a week for the past decade, 24/6: The Power of Unplugging One Day A Week—excerpted in the Summer 2020 issue of Humanistic Judaism Magazine. Earlier this year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York premiered her new live Spoken Cinema performance Dear Human. She lectures and performs worldwide on the relationship between technology and humanity. The Albert Einstein Foundation selected Tiffany for their book and initiative Genius 100 of people who are carrying on Einstein’s legacy. During Covid, Tiffany has been writing weekly newsletters and is hosting a weekly #ZoomChallahBake on Fridays with special guests and people from all over the world. For information on her book, baking, films, lectures, and her quarterly newsletter Breakfast @ Tiffany’s, please visit tiffanyshlain.com and follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Paul Golin, executive director of the Society for Humanistic Judaism, interviewed her by email in July 2020:

PAUL GOLIN: Your book spoke to me on so many levels. One thing it got me thinking about is the difference between “ritual” versus “practice.” In the Humanistic Judaism movement, we feel pretty confident about our rituals: utilizing meaningful recurrent words and actions to mark occasions. You do describe rituals around your family’s “Tech Shabbat,” such as cooking the same dinner every Friday night and reciting the blessing over the candles. But what your book is advocating for is a Shabbat practice. Turning off our technology for one day a week, every week, takes discipline. It’s a commitment that I imagine would be intimidating for many in our movement. Am I making a fair distinction between ritual and practice? Can you distill down the case you make for why people should take on the Tech Shabbat practice?

PAUL GOLIN: Your book spoke to me on so many levels. One thing it got me thinking about is the difference between “ritual” versus “practice.” In the Humanistic Judaism movement, we feel pretty confident about our rituals: utilizing meaningful recurrent words and actions to mark occasions. You do describe rituals around your family’s “Tech Shabbat,” such as cooking the same dinner every Friday night and reciting the blessing over the candles. But what your book is advocating for is a Shabbat practice. Turning off our technology for one day a week, every week, takes discipline. It’s a commitment that I imagine would be intimidating for many in our movement. Am I making a fair distinction between ritual and practice? Can you distill down the case you make for why people should take on the Tech Shabbat practice?

TIFFANY SHLAIN: I think of ritual as doing something to give meaning to that moment in your week, the year, or a rite of passage in your life — usually with others. I love that aspect of being Jewish. In fact, while I often have to replace all the God language in my head when I go to High Holiday services, I love knowing that Jews all over the world are doing the same thing at the same time and asking the same big questions…like, How do we all want to rethink our lives for the coming year? What would death feel like? How can we contribute more to our family and the world?

In terms of Shabbat, I savor the “ritual” of us all sitting down together at the same time as others all over the world, to be present together in an elevated way, to make a special meal, to tear at some sweet fluffy challah. We also ask the big questions around the table pertaining to what has happened in our lives and the world that week. That ritual is beautiful and nourishing and connects me to something larger than just myself.

I think of the word “practice,” the noun, as something more individual. Like I practice yoga. I don’t necessarily do it at the same time as others so it’s more personal and specific to me.

Now why should your community try taking a Tech Shabbat? I could give you so many reasons which I go deep and wide on the subject in my book 24/6 but here I will just offer a simple answer. I just turned 50 and it’s simply the best idea/practice/ritual I have ever brought into my life. It’s taking a core idea from Judaism, a day of rest, adapting it without the religious framework, and it’s the most powerful thing you can do each week to reset, recharge, reflect, what other R words can I throw in there? Rejuvenate…and also to radiate the best of yourself to yourself, your family and the world. It is the day where we are most ‘together,” as a family connecting with each other and even to our own selves. I can hear myself think and listen to that small inner voice-that has a lot of important things to tell you, but usually we keep life so noisy so we can’t hear it. When I turn off all the noise and input from the screens, from everything else, I gain a lot of insights and perspective I just don’t have room for when the screens are conduits to everything coming at us all the time.

I think Shabbat, a day of rest. is. the. best. idea. from Judaism.

PG: You’ve been very open about your approach to Judaism being cultural, not religious. You also live and work in community with fellow creative and highly-achieving Jews (and their Jew-adjacent friends and family members). Have you found that secular folks working in film and technology are more receptive to, or more rejecting of, ideas that emerge from religious tradition?

TS: Most of my friends in the creative or scientific fields do not respond well to the religious aspect of Judaism; neither do I. For me personally, as a feminist, I always found the patriarchal language troubling. If we truly want a more equitable society, why do we keep retelling stories that involve patriarchal power structures? It’s self-propagating. That has been a core issue for me in terms of the Jewish liturgy. However, the commitment to tradition and to ritual is something very interesting to me. I remember when I first met a young orthodox couple who didn’t use any electricity or money on Shabbat, I was fascinated. I asked them so many questions. I loved that they could live with such a clear boundary of work and rest. However, the more I asked, the more the reason landed on God, that this other force was telling them to do this. They were “obeying a commandment from God.”

I never thought a full day of Shabbat was available to me because I am not a religious Jew, but a cultural one. However, even saying, “I’m a cultural Jew,” doesn’t completely work for me because I feel like it doesn’t convey the deep love I have for the rituals and ideas.

I never thought a full day of Shabbat was available to me because I am not a religious Jew, but a cultural one. However, even saying, “I’m a cultural Jew,” doesn’t completely work for me because I feel like it doesn’t convey the deep love I have for the rituals and ideas.

Words hold a lot of power in them. The word “God” seems to hold so much patriarchal baggage for me. A good friend of mine, Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie (who runs Lab/Shul in NYC which is “God optional”), always told me to replace the word God with “universe” or “nature,” something that might speak to me more. I really do try to do that, but it is a lot of mental gymnastics while trying to literally translate the “prayer” book into a more open framework for me to get to the core of the idea. I think of Marshall McLuhan’s maxim, “The medium is the message.” The medium being “prayer”—which, if you don’t believe in that concept, immediately shuts a door to the important ideas in the book.

I would love to wrestle out a book of core Jewish ideas that are shared in temple without the religious patriarchal language. Someday, I will do that. The ideas are powerful; but the framework that holds them is an old way of thinking to me. Somehow singing the melodies work for me, perhaps because I don’t read Hebrew so it’s more abstract singing for me that is linking me in a powerful way to my ancestors. I know them by heart, not by head. Rabbi Noa Kushner from The Kitchen introduced me to a whole set of very ancient melodies and songs. They spoke to me deeply. It was so profound, how much they moved me and I seemed to sing them so easily. Some kind of ancestral heart memory coming through the song.

I have another very good friend, Rabbi Sydney Mintz (I apparently have a lot of rabbi friends), who told me that as a gay female rabbi, the fact that she stands in front of a large reform community at Congregation Emanu-El (a Reform temple where my family are members) opens up people to the possibility that the word God is open to interpretation. After centuries of old men leading prayers, the reality that people of different colors, genders and sexualities can lead a community has moved from the radical to the norm and given space for Jews in the pews to feel a different kind of connection to themselves, their rabbis, and their Judaism and their God.

However, for the word God, and much of stories, they are too steeped in a power structure and patriarchal dynamics that do not work for me. I would rather remove the tension that the word holds for me and liberate the ideas of Judaism.

Ironically, secularizing religious language strikes me as a really Jewish thing to do. I once heard a rabbi say that Judaism is a religion of behavior more than belief. You can be a good Jew and not believe in God, unlike in Christianity. If you are a good Christian but don’t believe in God, you aren’t Christian. Jews have “behavioral” rules for us to live a good life. Sometimes we break them, sometimes we bend them, but we are always striving.

I do feel a sense of awe when I look to the sky, think of the universe and the drama of nature.

The closest explanation of the way I feel (after years of searching for a way to articulate my ambivalence about the word and ideas around a “God”) was something I read about Einstein. Rabbis had been asking him, “Do you believe in God?” After quite a bit of back and forth, he finally wrote: “In my opinion the idea of a personal God is a childlike one. You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth. I prefer an attitude of humility corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and of our own being.” That pretty much sums it up for me. Thank you, Albert Einstein, for conveying the General Theory of Agnosticity.

Which reminds me of one of my favorite Jewish jokes: A Jewish family moves into a suburb and finds out that the only good school in the area is a Catholic school. While the parents are worried, education is most important to them, so they send their nine-year-old daughter Sarah there. On the first day of school, Sarah comes home excited by everything she has learned. “Mommy and Daddy, today I learned about the Holy Trinity: the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost!” Her parents, exasperated, look her in the eyes and says, “Remember, we’re Jewish, Jews have only one God…and we don’t believe in it!”

My husband Ken would prefer if I said I was agnostic, because that leaves room for the unknown. He is a scientist so perhaps his whole body of work (science) is trying to discover the unknown….so for them asking a question and not knowing is their own kind of religion.

My husband Ken would prefer if I said I was agnostic, because that leaves room for the unknown. He is a scientist so perhaps his whole body of work (science) is trying to discover the unknown….so for them asking a question and not knowing is their own kind of religion.

Now back to the concept of Shabbat. It is usually framed as the fourth commandment: God commanded a day of rest as he had done when he was “creating” the universe.

Let’s remove who “commanded” whom to do something. The idea of this one day off is a radical act. Before then, time had no period and life was just a long run-on sentence. A day off is what gave us the week and a time to work and a time to rest. One of the reasons I ultimately called the book 24/6 instead of Tech Shabbat was because I wanted the idea of one day of rest, six days of work to be at the forefront and not the word Shabbat, in case that may turn some people off to the idea because it sounds religious.

If you think of the 10 commandments as an ordered list of a good way to live, the 4th commandment is even above “Thou shall not kill.” That seems like a big deal. Perhaps if you take a true day of rest each week, you won’t kill.

This wisdom that you must take a true day away from what your mind focuses on all week is now backed up by so much neuroscience. Your mind needs different modes of being to be its most creative, productive and reflective. The mode we are always in now is on the screen and mostly reactive. By turning those screens off, you immediately snap into this other mode. I have found the internet puts me in a state of always wanting “more.” More email, more newsletter headlines, more notifications, more things. And it’s designed so you can’t ever get to the bottom of the internet. The business model is to keep your eyes glued to the screen. By turning the screens off, you reclaim your mind and your time and your presence. It’s very powerful.

Once my family and I started drawing a clear boundary from technology and work on our Tech Shabbat, now almost 11 years ago, I understood how profound this boundary of a full day off is for living a good life. It was liberating. Someone once said to me “You are the most ‘religious’ non-religious person I know,” because we have done this practice so faithfully.

A lot of my work is wrestling with how to take a brilliant Jewish idea and to detangle it from the religiosity so it can be more accessible. In the film I co-wrote with my husband Ken, The Tribe: The Unorthodox, Unauthorized History of the Jewish People and the Barbie Doll in 18 mins, the title of that film alone explains all my feelings on being Jewish.

First, I love being part of “The Tribe” of Jews. That’s the forefront, then I quickly say my approach will be unorthodox, and unauthorized, and that I am interested in history and our roots and I’m going to use something funny like the Barbie doll to tell that story (for those of you who don’t know, Barbie was created by a Jewish woman, Ruth Handler, so I use that framework that a Jew created the ultimate shiksa to explore American Jewish assimilation and identity). I made the film exactly 18 minutes long, a nod to the Herbrew word chai, which means “life” with the letter’s numerical values adding to 18, another nod to my love of the strong symbols and language. The film was also us exploring our American Jewish identity.

Being a blonde, blue-eyed Jew named Tiffany married to a blond, blue-eyed Jew named Ken, you can see why we made this film. This whole film was Ken and I wrestling out the way we felt about so many things. When I was making that film, Amichai shared with me that Israel literally means to wrestle or struggle with God, which I felt like so perfectly encapsulated the Jewish existence. That’s our very make up. Once again, I removed the word “God” from Amichai’s definition so I could engage with the idea. I was really making this for fellow unaffiliated/cultural Jews wrestling with their Jewish identity and was amazed how it spoke to all the denominations and the general public. It showed at orthodox, conservative, reform events, and premiered at Sundance and was the first documentary to be #1 on iTunes for narrative films. That’s an example of how liberating it can be to set free “religious” ideas.

I also made a film called The Making of a Mensch that is all about the Mussar movement from a non-religious perspective. Mussar is an old Jewish practice of character development. I had just made a film on the neuroscience of character development called The Science of Character and I was fascinated when I found out that there was a whole Jewish movement that focused on this that I’d never heard of. I think the reason I hadn’t known about it was because it was explored within mostly religious settings. When I pulled back that curtain, a whole world of ideas was suddenly open to me and I wanted to open it to everyone else! I remember when I showed the script to someone deeply steeped in the study of Mussar and he said, “I don’t know how you can talk about Mussar without talking about God.” How he could feel that a whole body of ideas that explored how to be a good person, how to be a mensch, could only be accessible if you were religious baffled me. These are important ideas to talk about, engage with, and teach, and they shouldn’t be confined to religious settings.

I also want to reclaim the words. I hated how mostly the word “mensch” was used to describe a boy or man. I went into the root of the word and found that it is a non-gendered word and made a point in the film to talk about menschness for all genders. It is the highest compliment I give someone and enjoy especially bestowing it on women.

(Btw, people can watch all these films at tiffanyshlain.com)

PG: What do you think we can or should be telling such folks about Humanistic Judaism that might be meaningful or exciting to them?

TS: To try a full day of rest. It is the most exciting thing I have ever done. Truly. Most people think of Shabbat as a special dinner or lighting the candles together. That part is social and fantastic but it is just the door or the entrance to the super potent aspect of Shabbat, a full day of rest. Where Shabbat dinner is social and vibrant, Shabbat day is more quiet and inward and reflective. I want to live in a world where more people value and practice reflection and gaining perspective. We are living in 24/7 reactive society. Especially now with the pandemic. My seventeen-year-old daughter Odessa said to me in the heat of the pandemic, that first month of lockdown, that Tech Shabbats where the only day she didn’t feel like we were in lockdown. This comment moved me. Was it that that day still felt the same? Was it the protection from all the stressful news? Was it that we were together and present with each other? Was it that we all feel “liberated” on our Tech Shabbats from being so “on”?

We need to create space to think and be without all the new stimulation and input from the outside world. There is a lot of value of the inner work that comes from taking a full day off the screens, each week.

During quarantine, I’ve started a new ritual: hosting a Friday-morning Zoom challah bake. It literally connects me with people all over the planet, all doing the same thing at the same time. As we mix and knead, we talk about how we’re doing and discuss bigger ideas and everything going on with the pandemic, racial justice, and the upcoming election. Every time, we have a guest baker — past guests have included Roxane Gay, Angela Duckworth, Rabbis Sydney Mintz and Amichai Lau-Lavie, Krista Tippett and many others — to share the wisdom. It’s been fantastic. Would love to have your community join us.

PG: Much of your work organizes lots of people around big ideas, from the Webby Awards to Character Day. Yet your Tech Shabbat feels much more intimate, developed primarily around friends and family rather than an organized community. Must “living 24/6” be more individualized by definition? Or could you see (non-religious) communities organizing around it?

TS: Yes! I think it is individual but there are definitely whole communities both Jewish and non-religious that are doing it together. It is intimate but not detached from others doing it. We did a whole challenge to my community to try unplugging for four weeks in a row with me and it went great. Especially in the time of Covid when we are on screens more than ever, the demand for the book and ideas from the book have only grown. We are going to need to create more boundaries and protected spaces in a world that is now blurring everything with screens…and when most of school and also social activity is also on screens now too. How do we create special spaces and boundaries in our lives that can allow you to truly rest and reset?

My husband Ken first introduced me to Shabbat (he had grown up with Friday night Shabbat dinners and then had lived in Israel for graduate school where the whole country shuts down for Shabbat and grew to crave and love it). When we first met we would do partial versions of shabbat. Then the iPhone came out in 2007 and that blurred the line of everything with the screens, work, rest, and leisure that began to feel like work when you had to constantly document, post and check it. Then in the beginning of 2010, not long after my father died and my daughter was born within days, it was a very dramatic period in my life that made me rethink how we were living. Reboot, an organization I have been a part of since its founding (a group of filmmakers, artists, comedians, and writers that spend a lot of time rethinking Jewish rituals in new ways) came together to rethink Shabbat with the first National Day of Unplugging in 2010. That was when we turned off screens for a full 24 hours. It felt so good, our family never stopped doing it.

PG: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

TS: I have been very excited to learn more about Secular Humanistic Judaism. I never gravitated to the word secular because for some reason it felt cold to me (sec, like cut, or divide). Although I do appreciate people who use the word. However, when you reminded me of the word humanistic, it suddenly felt warm and inviting. Ken and I had Saul Perlmutter over for Shabbat after he regaled us with stories of an ever expanding universe, mostly what I was interested in hearing him talk about was the humanistic temple he grew up in. I loved hearing how they approached Judaism. We both marveled that it hadn’t taken off in the Bay Area. Seems like fertile soil for that kind of Judaism. I longed for it. Then I met you. And learned there are many others…and chapters all around the country. And now I feel less alone. In The Tribe, one section of the film explores how Jews throughout history have felt like outsiders, then we say, “Maybe that’s why we created a bread with only an outside,” as we show a bagel. I have always felt like an outsider at most temple services knowing that many of the words that I am chanting are not in line with my thinking — even though I feel so connected to the melodies and of course love seeing people there…and listening to an amazing sermon linking core Jewish ideas to things we are wrestling with in society. So my final thoughts for you…. finding your community lets you feel less like an outsider amongst the outsiders.

—

This interview originally appeared in an abridged format in Humanistic Judaism Magazine Summer 2020 issue.

Leave a Reply