This article is an excerpt from the Congregation for Humanistic Judaism of Metro Detroit weekly newsletter.

WHAT SIMCHAT TORAH CAN TEACH US ABOUT JEWISH DIVERSITY

by Rabbi Jeffrey L. Falick

Here’s a little Jewish holiday history trivia question:

What is the newest major holiday on the Jewish calendar (excluding twentieth century commemorations related to Israel and the Holocaust)?

The answer is (I feel like there should be a drumroll here) … Simchat Torah.

An appendage of Sukkot, Simchat Torah is not only the newest holiday on our calendar, it is an entirely diasporan (outside the land of Israel) medieval invention. Since it is attached to Sukkot, arguably one of the oldest Jewish holidays, many people think it’s just as ancient. The story of how it developed is worth understanding because of what it says about Jewish diversity and the evolution of Judaism(s).

Just in case you don’t remember what Simchat Torah is all about, allow me to provide a refresher.

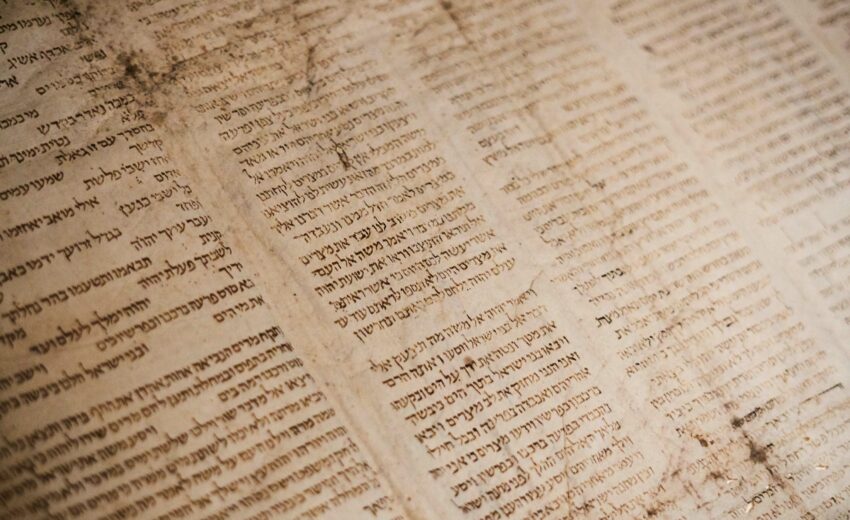

Simchat Torah (literally, “Rejoicing in the Torah”) is the final holiday of the Sukkot season though it is not really part of Sukkot at all. It is distinguished by a couple of major rituals, both of them involving the Torah scrolls. The first involves processions and dancing. On both Erev (the eve of) Simchat Torah and the daytime version of the holiday, the scrolls of the Torah are removed from the Ark and paraded around the synagogue seven times. This is accompanied by raucous dancing and little children waving flags.

Torah scrolls. The first involves processions and dancing. On both Erev (the eve of) Simchat Torah and the daytime version of the holiday, the scrolls of the Torah are removed from the Ark and paraded around the synagogue seven times. This is accompanied by raucous dancing and little children waving flags.

The second major ritual is the reading of the Torah scrolls during which the annual cycle concludes with the end of Deuteronomy and begins anew with Genesis.

So much for the refresher. On to the story of how it developed. Stick with me here because it’s a rough road.

As I’ve pointed out, Simchat Torah is our newest holiday, developed in the diaspora. And yet, it is also connected to one of our oldest festivals, Sukkot. That holiday is mentioned in several places in the Torah, notably Leviticus 23:39:

“Mark, on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you have gathered in the yield of your land, you shall observe the festival of [Sukkot] for seven days: a complete rest on the first day, and a complete rest on the eighth day.”

This verse introduces the seven-day holiday of Sukkot and tells us that the first of its seven days is a “complete rest” day. But then it mentions an eighth day—not part of the seven days of Sukkot—also  considered a “complete rest” day. Other Torah passages call that eighth day Sh’mini Atzeret, the Eighth Day Assembly.

considered a “complete rest” day. Other Torah passages call that eighth day Sh’mini Atzeret, the Eighth Day Assembly.

So far this is not that complicated. We have a “complete rest” day that kicks off Sukkot’s seven days and then we get to a “complete rest” day that serves as a big Assembly day, a final addition, of sorts, to Sukkot.

By now you are scratching your heads asking, “Where is Simchat Torah?” The answer is that it’s about to evolve from a very weird Jewish custom—one that developed in the diaspora—on which additional “complete rest” days were added to several holidays in the diaspora only. They added these extra days to deal with anxieties about some uncertainties in their diasporan calendrical calculations.

In any case, the effect of this custom upon Sukkot was to turn its second day into a “complete rest” day in the diaspora (only). And its effect upon the Eighth Day Assembly was to expand it into two “complete rest” days which, in turn, yielded a previously non-existent Ninth Day Assembly.

And, to be frank, that good old Eighth Day Assembly was already one of the most extraneous holidays on the calendar. What it did not need was a Ninth Day.

And yet, there it was.

Here we have arrived at the penultimate stage in the medieval creation of Simchat Torah. Hint: it’s all about finding something to do on the all-new, even-more-boring-than-the-original, Ninth Day Assembly. The something to do that emerged on that day was related to another unique custom in the diaspora, that of reading the entire Torah every year. (In the land of Israel they took three years to get through it). Given that concluding and re-starting the annual reading took place in autumn, it appears that the diaspora-only Ninth Day Assembly evolved into Simchat Torah.

Et voilà! A new holiday!

Why did I devote my weekly congregational newsletter commentary to this little known origin story of a holiday that is barely perceptible to most non-Orthodox Jews and little observed among us Humanistic Jews? Because it serves as a very important reminder that Judaism is not one “thing” from which we alone, among all other Jews, have deviated.

Today’s Jews and their Judaisms constitute a complex set of peoples and cultures and sub-cultures that have changed and mutated over many centuries and millennia. Culturally analogous to biological evolution, Jews and their Jewish cultures (their Judaisms) also have extinct and extant antecedents:  Israelite, Judaean, Rabbinic, Ashkenazi, Sefardi, Reform, Orthodox, secular, Humanistic, and dozens more. Each is the product of specific historical contexts and group needs. Each is completely legitimate and none may lay claim to any greater authenticity.

Israelite, Judaean, Rabbinic, Ashkenazi, Sefardi, Reform, Orthodox, secular, Humanistic, and dozens more. Each is the product of specific historical contexts and group needs. Each is completely legitimate and none may lay claim to any greater authenticity.

Before I conclude, here’s one last mutation of Simchat Torah to seal my point.

It’s not entirely clear when Jews in Israel adopted the annual cycle for reading the Torah, but whenever they did so, there was no Ninth Day Assembly in Israel. How, then, would they celebrate Simchat Torah?

They did it on the Eighth Day Assembly holiday, a completely different day than everyone in the diaspora.

And there you have it. A holiday that’s all about the Torah that’s not mentioned in the Torah is the only holiday celebrated on two completely different days depending upon whether one lives in Israel or in the diaspora. And no one says that it’s illegitimate or inauthentic and everyone accepts it.

Just like we should with so many of our other differences.

Leave a Reply