Lessons Learned at the Foot of Mt. Sherwin

Rabbi Miriam Jerris

This article was written in 2007 as a tribute to Rabbi Sherwin Wine, founder of Humanistic Judaism, shortly after he was killed in a car crash. For today, it has been heavily edited to include only the lessons learned rather than the consequences of those lessons for the future of Humanistic Judaism

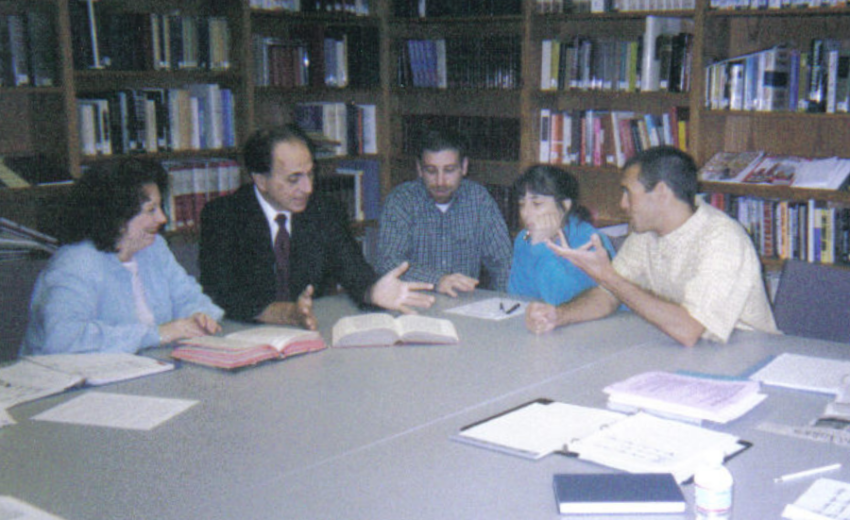

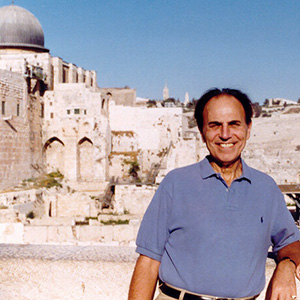

A great leader has died. Our great leader has died. Rabbi Sherwin T. Wine was a remarkable man. He was a prophet and the founder of Humanistic Judaism, our Jewish home. It is easy to imagine him as a mountain, tall and majestic – and for more than 40 years of my life I sat at the foot of Mt. Sherwin. He was my rabbi from the time I was eleven years old. He presided at my Bat Mitzvah, my confirmation, my wedding (both of them), the naming ceremonies for my children, their mitzvahs and confirmations and my daughter’s wedding. He supported me during the difficult times through the deaths of my brother, my grandparents, and my mother. I cannot tell you how many times I heard him speak, the hours of lectures, holiday and Shabbat sermons, inspirational seminars, and rabbinic classes. His office was across the hall from mine. His voice and laughter were constant companions. His death changed my life dramatically. His vision, his ideas and his LIFE changed me and my life profoundly and forever more.

Although I have had more direct and consistent contact with Sherwin Wine than many, I also know that there are countless people, probably thousands of people who have had personal contact with him and made connections to him and so can identify with some of what I just said. This identification creates a common ground for the lessons learned at the foot of Mt. Sherwin. On this, the anniversary of his birth, we pay loving tribute to our founder, using the lessons he taught to inspire us to establish a lasting legacy, to live authentically and courageously as Humanistic Jews, with dignity and hope.

The Talmud gives us the teaching of our rabbis. When we read, Rabbi Hillel or Rabbi Gamliel or Rabbi Akiva said, we are learning what Rabbis Hillel, Gamliel, and Akiva and their followers taught. What we read in Hebrew is “rabi akiva omer (rabbi Akiva said).” This is the school of Rabbi Sherwin Wine. Sherwin’s Hebrew name was Shimon ben Tsvi. In creating a Hebrew acronym from the first letters of his name — Resh, Shin, Bet and Tsadee — you have Rashbats (with thanks to Rabbi Avi Pascal from our Israeli program and Rabbi Adam Chalom for sharing). And this acronym creating was done regularly in ancient times Rom Bom for Maimonides is a well-known example. Now we have Rashbats omer, Rabbi Shimon ben Tsvi said — These are the lessons I learned at the foot of Rashbats.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #1: Integrity

Integrity is saying what you mean and meaning what you say. This is a simple statement that has revolutionized the tapestry of modern Judaism. It means that no matter how much we love Judaism, Jewishness or being Jewish, we cannot say things liturgically that we do not believe.

In Sherwin’s words: “Integrity is a harmony between our words and our behavior. Our convictions and our actions mirror each other… Integrity can also mean that there is harmony between what we think and feel and what we say…

With the Haskalah, the Jewish enlightenment, it became increasingly clear that the evidence for the existence of a personal god, the god of the Hebrew Bible was unconvincing. And after the Holocaust? Sherwin said that the nicest thing you could say about God after the Holocaust was that he didn’t exist. This concept of integrity is the distinguishing feature of Humanistic Judaism.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #2: We are our behavior

When Rabbi Wine taught me this, it was an “aha” moment, almost as significant as when I first learned about Humanistic Judaism. I learned this lesson when I was a very young adult. It taught me a whole new way of evaluating people and their true intentions. Don’t just listen to what people tell you, watch what they do.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #3: Believing is better than Non-Believing

One of my favorite essays that Rabbi Wine ever wrote carries that title. It was first published in the Summer, 1985 issue of Humanistic Judaism. In it, he makes the case that describing Humanistic Judaism in terms of beliefs rather than “unbeliefs” empowers us.

As believers we: refuse to be an unbeliever; focus on the positive; know that the message, OUR message is  important; offer positive alternatives; do not worry about being unfashionable; do not resent the enthusiasm of our opponents; turn negative situations into positive ones; choose to reverse roles and make our desires clearly heard; seek out other believers for mutual support; give personal testimony all the time.

important; offer positive alternatives; do not worry about being unfashionable; do not resent the enthusiasm of our opponents; turn negative situations into positive ones; choose to reverse roles and make our desires clearly heard; seek out other believers for mutual support; give personal testimony all the time.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #4: “I Don’t Know” is a Legitimate Response to a Question

Sherwin told us that “’I do not know’ is a brave and dignified answer, especially when it is true.” For Sherwin “I don’t know” was the pithy remark that represented the entire philosophical system of empiricism, scientific inquiry and affirming the use of reason as the best method to discover truth. This forms the foundation of the Humanism part of Humanistic Judaism. This grounds us in the natural world.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #5: Alphabet soup is delicious

After Sherwin founded the third or fourth organization that he identified with letters, we began to tease him about the alphabet soup. We had the BT, SHJ, AHR, LCSHJ, NACH, HI, IFSHJ and IISHJ. All these organizations Sherwin had a hand in founding and organizing.

Sherwin had a profound vision and he wanted to spread the word, not as an evangelist or missionary, rather out of a sense of conviction that what he believed was shared by others. He also fundamentally believed that people need projects to excite and engage them. And members get energized because there is a new idea, a new dream, a new organization, and a new project.

I caught the bug when I was a young married woman and a new member of the Birmingham Temple in the Detroit suburbs. The excitement I felt when we’d receive a call from someone just finding out about Humanistic Judaism was like a contagious disease that I wanted to catch over and over again. And we discovered that it was much better to do together what others were doing alone. We met many people, formed friendships, some deep and life-long and we spread the word.

Rashbats omer — Lesson #6: Human dignity is the purpose of life

For Sherwin Wine, the purpose of life was human dignity. When asked about the meaning of life, Sherwin had his answer. It was human dignity. He defined dignity as “enabling people to become the masters of their own lives and respect this potential in others.” For Rabbi Wine, dignity included autonomy, freedom, competence, respect, and hope. Achieving dignity is a life-long process and it necessitates living Sherwin’s Life of Courage. Rabbi Wine said “the sign of dignity is self-respect. The evidence of dignity is that my behavior follows a path of consistent principle and gives me control over the direction of my own life. Dignity is not a right. It is an achievement.”

Rashbats omer — Lesson #7: Hope is a Choice

Rabbi Wine’s behavior optimized his optimistic approach to life. He understood and exemplified that the one thing we have control over in life is our response to life’s realities. It is our CHOICE. And he chose hope. There were times when I felt his view of the world was naïve and unrealistic. However, more often than not, I found that his insistence on the dream ultimately made it a reality.

Sherwin taught us that: “Hope is also a way of coping with life. It is the other side of self-esteem. It is the affirmation of competence. It is an invitation to respect. When we take pleasure in our own strength, when we enjoy our own power, we release their possibilities. We play the adult. We take responsibility.  We choose that style. It is the only role that rescues us from infancy that gives us dignity.” For Sherwin hope was an attitude toward life. He affirmed: Without hope even the day is like night. And with hope even the darkness becomes light.

We choose that style. It is the only role that rescues us from infancy that gives us dignity.” For Sherwin hope was an attitude toward life. He affirmed: Without hope even the day is like night. And with hope even the darkness becomes light.

Sherwin was a philosopher, and the strength of his poetry was in its philosophical message. For his 60thBirthday Sherwin wrote about hope. This selection was read at his memorial service at his request.

“I believe.

I believe in hope.

I believe in hope that chooses-

that chooses self-respect above pity.

I believe in hope that dismisses-

that dismisses the petty fears of petty people.

I believe in hope that feels-

that feels distant pleasure as much as momentary pain.

I believe in hope that acts-

that acts without the guarantee of success.

I believe in hope that kisses-

that kisses the future with the transforming power of its will.

Hope is a choice,

never found,

never given,

always taken.

Some wait for hope to capture them.

They act as the prisoners of despair.

Others go searching for hope.

They find nothing but the reflection of their own anger.

Hope is an act of will,

affirming, in the presence of evil,

that good things will happen,

preferring in the face of failure, self-esteem to pity.

Optimists laugh, even in the dark

They know that

hope is a lifestyle

not a guarantee.”

Sherwin knew what could essentially change the face of our organizations – that success is dependent on choice, will, and attitude. These are the things over which humans have control. Rabbi Sherwin T. Wine, Shimon ben Tsvi, Rashbat, knew that inherently, fundamentally, and pervasively. We are the recipients of that legacy – the torch belongs to us. Where is my light? My light is in me. Where is my hope? My hope is in me. Where is my strength? My strength is in me. And in you.

Thank you for sharing this message.

I’m at a loss as to why Humanistic Judaism omits love as a reason for existence. Humanists seem to go through contortions to avoid this basic human emotion. For me, every human situation can be simplified into, there is love or there is no love. I know where I want to stand. Where are the Humanists?